Colonial Precedent on Race (SC) - Victory and Vindication

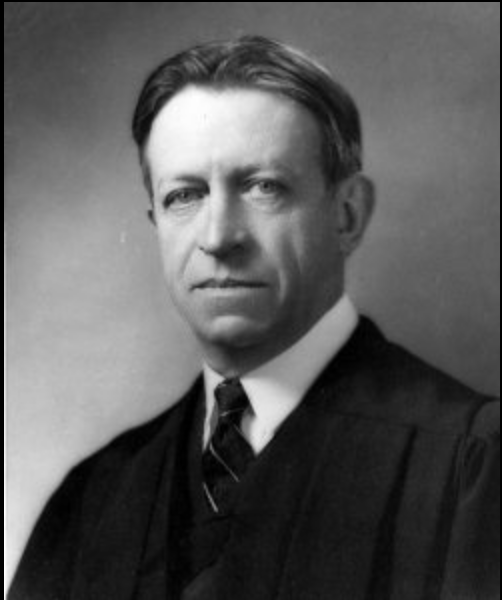

My recent virtual jaunt led me to a memorable day of vindication – even the weather was compliant. After a rainy spell in the Low- country, the sunshine burst through the clouds in brilliant splendor on April 11, 2014, and the Four Corners of Law, at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets, teemed with activity. Members of the Charleston community gathered – they came to reclaim the past and render restitution to one whose moral compass and judicial acumen dictated unpopular positions as a United States District judge in South Carolina from 1942 to 1952. His rulings and decisions often ran counter to those of many of his peers. On this momentous day individuals arrived from near and far, North and South, and streamed into the courtyard of the Federal Building to pay tribute to one now acknowledged as a fierce defender of Civil Rights, once “Enforcer of Separate but Equal.” The atmosphere was pregnant with anticipation– something was in the air that morning. Esteemed members of the nation’s legal community were assembling. They were joined by Charleston leaders and politicians, and distinguished members of the Charleston County and State Bars and judiciary; all there to symbolically bring Judge J. Waties Waring home.

I got caught up in the euphoria of anticipation. As a court reporter for 28 years in the Charleston Master- in-Equity Court, I was sensitive to the drama and intrigue of a courtroom. I had witnessed the nimble and strategic maneuvers of experienced jurists and judges in control of their courtroom and now recognized the same feeling. There were some who streamed in among those attending the ceremony. I took my seat and slipped unnoticed into my virtual world. From here I moved freely in observation from the present to the past. From time to time I paused — I wondered:

Is anyone asking the questions I deem important?

What really brought us to this time and place?

How is this posthumous homecoming going to repair and restore lives inflicted by pain and separated by ideologies?

Is our collective legacy a matter of consideration as our daunting past produces tensions in our day-to-day affairs?

Is there hope that the present will allow us to reconcile differences and resolve challenges from the past?

Lastly, what about the future…what about the future? Will the future be consumed with issues of the past?

Questions like these occupied by thoughts as I contemplated the significance and weight of the moments unfolding.

Let me move on…the ceremony was about to begin. The racially mixed assembly, some with families going back four or five generations, sat silently, waiting. A few others engaged in light-hearted, controlled banter. Everyone must have been fully aware of the history of race relations in these United States and here in Charleston, but I sensed those gathered felt at home. Charleston was their home. Each person seemed to have a clear understanding of place, connection, and social standing in the community. As I sat and waited – I turned the pages of the booklet handed to me then I drifted away again. But – but bring Judge Waring home from where? Where was he, and why was he there? His death and burial occurred in 1968. These questions were about to be answered. The word was that many in his beloved community felt betrayed by his unrelenting defense and final victory on issues of race and equality, which drastically changed certain accepted norms in Charleston and in the South.

As the story unfolded that day, there was hearsay evidence of ostracism, rejection, threat of bodily harm. A stone had been hurled through the window of the Judge’s home, and a cross was burned on his lawn. Eventually, the Judge and his family moved to New York, where he spent the remainder of his days after retiring from the bench. It has taken both the legal and Charleston communities this much time after his passing to marshal the will and resolve of the people to welcome and vindicate him as the Civil Rights stalwart that he has become.

Upon reflection of the past, my memory was refreshed of South Carolinas’ history. A distinguished historian wrote that the Carolinas adopted the “Barbados Model” of governance. The early Barbadian settlers introduced what they deemed a tested and tried system to the new colony in 1670. Charleston’s society became woven together with many colonial threads—intertwined, sometimes entangled. The much-maligned Goose Creek men (mostly Barbadians) eventually lost their power and control during the Proprietary Period. However, many laws and precedents regarding race survived them into the present.

Blacks in America, especially in Southern states, weren’t granted the rights and privileges awarded to whites, including the right to education. Slaves Laws from colonial Barbados were modified and adapted in the Carolinas, as were many other social mores and practices. “Racial separation in all aspects of public life was the norm in state and local government.” During the 1930s and 1940s there was great racial unrest. Blacks were striving for civil rights, the right to vote, and for equality in education. Courageous blacks rose up to challenge systems of injustice and inequality on many fronts. Those who dared to confront the inequities of the time were ensnared in vicious webs of retribution and retaliation. Bodily harm and intimidation were prevalent under the suppressive laws of this era. With little or no power, blacks had few advocates and were at the mercy of those in power.

It’s at this juncture of history that Judge Waites Waring arose to champion the cause of the masses – the black masses. In a series of racially charged cases: Duvall v. Seignous, Wrighten v. Board of Trustees of the University of South Carolina (1947); Elmore v. Rice, a case involving Isaac Woodward Jr., a returning black World War II veteran, and others, he emerged into a place of prominence in Southern courts. Some esteemed him and others despised him, but he was guided by duty, equity and justice, and by an indefatigable zeal to enforce the rights of black litigants. That was contrary to the status quo.

One of the cases that stood out in Judge Waring’s illustrious career is the Briggs v. Elliott case. When this case came before him he saw it as an opportunity to test the theory of a previously decided case Plessy v. Fergusson which became the basis of the “Separate but Equal” theory in education for blacks. He was proven right, and “Separate but Equal” was reversed. Descendants of members of the black plaintiffs in that landmark case were present at the gathering to honor the memory of the Judge who represented their cause and won. This case is recognized as one of the decisions which led to the dismantling of segregation in the South.

There was a short pause – the chairman waited for the arrival of one more dignitary – the Attorney General of the United States, the Honorable Eric Holder. He made his way through the crowd flanked by members of the Secret Service. This was a particularly poignant moment. The Attorney General, himself no stranger to verbal jabs and aspersions, was here to participate in the ceremony to honor Judge Waites Waring, a defender of Civil Rights who fought and won a major victory and destabilized a system that historians say was instituted by Barbadians in 1670.

The ceremony began. One by one the speakers took their places on the stage. Each one recaptured segments of the past with vivid, graphic and compelling stories of determination and resolve, courage and perseverance, then victory. I sat mesmerized as each word wafted over the heads of those seated from the elevated platform where each speaker stood. I checked my internal list of questions to see if they were being answered.

Finally came the unveiling of the Waring Statue. As the purple shroud was lifted, and it seemed the real stature of the Judge was on exhibit for all to see. The audience was instructed to remain in place until the dignitaries took their leave. The people complied. As my virtual stop came to an end, I reflected on how the past continues to prance on life’s stage and jeer the present and future in unforgettable displays of irony. Attorney General Eric Holder’s parents hailed from Barbados and he openly acknowledges his connection and link to Barbados. As British poet Alexander Pope penned, “Hope springs eternal.” The future will present ongoing race-related challenges; we’re assured of that. We can be motivated and inspired by the lives and examples of Judge Waites Waring and the plaintiffs in Briggs v. Elliott.

Rhoda Green, CEO / Barbados and the Carolinas Legacy Foundation